The True Story of Thanksgiving

Interested in History? Search Liberal Arts & History programs below!

Table of Contents

In 2023, a projected 55+ million1 people in the United States will take to the road and sky to celebrate Thanksgiving with family and friends. Children will don Pilgrim hats in school plays, and large inflated turkeys will bobble and glow on front lawns.

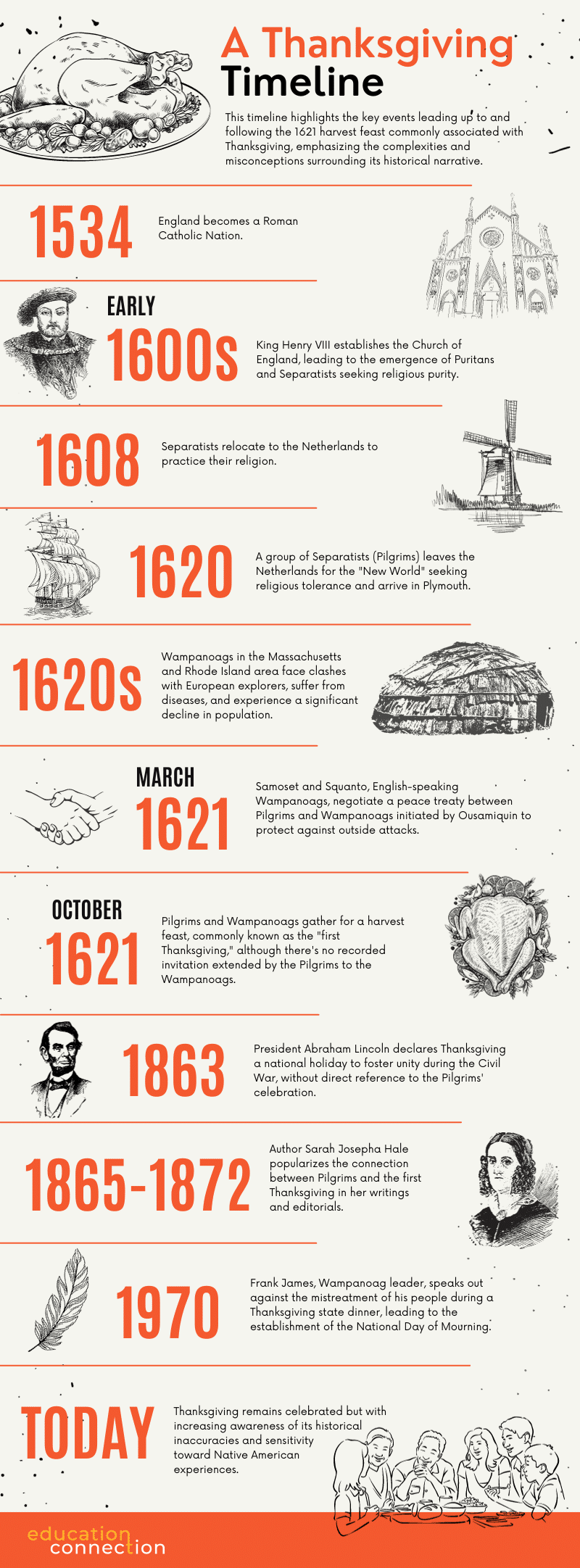

The story of Thanksgiving has morphed into an inspiring story of welcoming indigenous peoples and grateful colonists who come together in friendship and peace. But historians argue that this story is replete with falsehoods that sugarcoat the complexities of the events before, during, and after the feast of 1621.

The Pilgrims

To better understand the dynamics of that feast in 1621, it could be helpful to have a better understanding of the group of 102 men and women who landed in Plymouth in 1620.

In 1534, England was a Roman Catholic Nation. When King Henry VIII came into power, he established a new national church known as the Church of England. While based on Catholicism, he and later his daughter Elizabeth introduced changes to differentiate this new church from the Roman Catholic Church.

Some people felt that the changes were not enough, however. They wanted to practice a more “pure” version of Christianity that was simpler and less structured. These individuals became known as “Puritans.” Another more radical faction, identified as “Separatists,” went a step further, insisting that the Church of England was irreformable. They called for the creation of entirely new and separate church.

Both groups were persecuted since, in the early 1600s, it was illegal to be part of a church other than the Church of England. The Separatists eventually relocated to the Netherlands, where they were able to practice their religion. However, after about 10 years they felt that this solution was unsatisfactory, and they decided that a small group of them would leave the Netherlands to establish a settlement in the “New World” that would tolerate religious freedom.

The Pilgrims, however, were not for religious freedom. They believed their way of worshiping God was the only way, and they were intolerant of any digressions. In fact, while their initial plan was supposedly to settle in the northern part of the Virginia Colony—which was actually the first permanent settlement by the English in North America—some believe that they never planned on settling there at all, wanting instead to be as far from Anglican control as possible.

The Wampanoags

The Wampanoags tribe, one of many nations of Native Americans living in North America when the Pilgrims arrived, have lived in the vicinity of what is now Massachusetts and Rhode Island for over 12,000 years. In the 1600s, there were nearly 70 Wampanoag villages spread across that area.

The Wampanoag were semi-nomadic, moving seasonally among fixed sites. They hunted and fished and cultivated crops such as corn and squash.

Each Wampanoag tribe had its own leader, and they, in turn, answered to the Wampanoag “Massasoit,” or “paramount leader.” When the Pilgrims arrived in 1620, that leader was Ousamiquin.

While the Wampanoags were the first tribe that the Pilgrims encountered when they landed in Plymouth, the reverse is not true —the Wampanoag’s interactions with Europeans did not start with the Pilgrims. For years, English and French fishermen and explorers had clashed with the Wampanoags, capturing them and other Native Americans for slave trade. These explorers also brought with them disease. Between 1616 and 1619, a period known as the “Great Dying,” an outbreak of disease ravaged the villages of the Wampanoag, wiping out up to 90% of the population.

In fact, Squanto, a member of the Wampanoag who spoke English and was known for helping the pilgrims survive in their new environment, had learned English because he had spent years in captivity in Spain and England.

The Meeting of the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag

The Pilgrims and Wampanoag did not encounter each other right away. It wasn’t until March 1621 that English-speaking Samoset and Squanto entered Plymouth carrying a message from Ousamiquin, who wanted to negotiate a peace treaty with the Pilgrims. In the subsequent treaty , the Pilgrims and Wampanoags agreed not to harm one another and to protect each other from outside attacks.

According to some historians, this treaty was initiated by Ousamiquin not so much as a gesture of friendship but as a way for him to fend off attacks by the Narragansett, a neighboring tribe who had been trying to subjugate the Wampanoag people. Despite periodic episodes of tension, both parties honored the treaty until after the death of Ousamiquin in 1661. (The subsequent fallout between the Wampanoags and New England colonies that led to the devastating King Philip’s War is a story for another article.)

The treaty might have saved the Plymouth colony from destruction. The first winter the Pilgrims experienced was brutal—about half of them died from the harsh conditions that they were unused to. In the spirit of cooperation fostered by the treaty, the Wampanoags taught the Pilgrims how to grow crops such as corn and beans and generally how to survive in their new environment. By October 1621, they had built a number of crude houses and common buildings and had propagated a bountiful harvest.

Which takes us to the events of what is known as the first Thanksgiving. Perhaps one of the biggest misconceptions surrounding the story of Thanksgiving is that the Pilgrims intended their celebration to include the Wampanoags. In fact, there is no record of the Pilgrims having invited the Wampanoags to their feast. Many accounts of the festival maintain that the reason the Wampanoags were even there at all was that they heard the sound of guns being fired in celebration and came to investigate. The ensuing three days could likely have been characterized more by tension and suspicion than friendship and goodwill.

Another myth is that these festivities constitute the “first” Thanksgiving in the New World. In reality, Native Americans in North America had been giving thanks for bountiful harvests for years. And there are recorded accounts of thanksgiving celebrations in the U.S. that occurred long before the Pilgrims arrived. In fact, some consider the first thanksgiving to be the 1556 celebration between Spanish settlers and about 200 Indians in St. Augustine, Florida .)

Want to share this image on your site? Just copy and paste the embed code below

The Evolution of Thanksgiving

In 1863, during the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed Thanksgiving a national holiday as a way to foster unity between the north and south. But Lincoln’s proclamation did not mention anything about the Pilgrims or the celebration that took place in 1621. So how did the Thanksgiving we celebrate today become equated with the story of the Pilgrims and Wampanoags in 1621?

It may well likely have been due to the influence of author Sarah Josepha Hale. Hale was the author of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” but her achievements go far beyond the penning of that rhyme. She was the writer and editor of an influential women’s magazine, Godey’s Lady’s Book, and is also attributed as having been the driving force behind Lincoln’s Thanksgiving proclamation. For years she had used her writings to urge politicians to establish Thanksgiving as a national holiday. A letter she wrote to President Lincoln about the matter is often considered to be instrumental in Lincoln’s decision.

Hale herself made the connection between the Pilgrims and the first Thanksgiving in an editorial she wrote in 1865: “To the Eastern colonies we must look for the beginning of this custom. The Pilgrim Fathers incorporated a yearly thanksgiving day among the moral influences they sent over the New World.” And in 1872 she wrote a hymn in tribute to Thanksgiving, referencing the “faithful Pilgrim Fathers” and “Their first Thanksgiving Day.”

The connection was repeated by newspapers and other magazines, began appearing in school textbooks, and took hold. We’ll never know for sure why Sarah Hale made this connection, or whether she was indeed the one responsible for popularizing it. By some accounts, it was a group of pilgrim descendants who planted the seeds in 1769 because they felt that their cultural authority was eroding and that New England was becoming less relevant with other colonies. Whatever the origins, equating Thanksgiving with the Pilgrims and Wampanoags perpetuates a story fraught with inaccuracies and insensitive to the realities of the plight of Native Americans in this country.

National Day of Mourning

In 1970, Frank James, then leader of the Wampanoag, was invited to speak at a Thanksgiving state dinner marking the anniversary of the Mayflower. But James would not be silenced about the treatment of his people, and he wrote a scathing account of how the Pilgrims stole food, desecrated graves, and spread disease among his people.

The organizers found the speech to be inappropriate and was “uninvited” to the dinner.

Instead, he led supporters to Cole’s Hill, next to the statue of Ousamiquin, and read his speech. This became the first official National Day of Mourning, which has been celebrated in that location every day since.

Conclusion

So where does all this unraveling of history leave us? Should we stop celebrating Thanksgiving altogether? Not necessarily. But it is important to understand what really happened, both before and after 1621, to be cognizant of the misconceptions that have been perpetuated, and to be sensitive to the lasting effect the myths of Thanksgiving have had on the Wampanoag and Native Americans as a whole.

Sources

1Projections by AAA: https://newsroom.aaa.com/2023/11/aaa-thanksgiving-holiday-travel-period-forecast/#:~:text=WASHINGTON%2C%20DC%20(November%2013%2C,the%20Thanksgiving%20holiday%20travel%20period*.

Financial Aid Info

- Your Guide to Federal Student Loans

- Grants and Scholarships

- Military Benefits

- Private Student Loans

- Repaying Student Loans

- Student Loan Consolidation

- Education Tax Credits | AOTC & LLC

- 15 Military Scholarships to Apply For in 2023

- Grad School Scholarships

- 12 Graduate Scholarships for DACA Students in 2024

- Graduate Scholarships for International Students

- Grants for Women

- Guide Schools & Scholarships for Students with Disabilities

- Guide Tribal Colleges and Scholarships for Native Americans

- 8 Adult Scholarships for Adults Returning to School

- How to Earn Credit for College with Life Experience

- The Psychology of Lying

- 36 Companies That Pay For College

- FAFSA: Parent and Student Assets

- How Do You Get Student Loans Without a Job?