You are a leader in the same Army that persevered at Valley Forge, held its ground at the Little Round Top, turned the tide of a war at St. Mihiel and began the liberation of a continent at Omaha Beach. You lead soldiers from the same Army that burst out of the Pusan Perimeter, won against enormous odds at the Ia Drang Valley, fought with determination at Mogadishu and relieved terrible misery in Rwanda. Leaders like you and soldiers like yours conducted intense combat operations in Afghanistan while only a short distance away others supported that nation’s rebuilding and still others fought fires in the northwestern US. Throughout the history of the Army the NCO has been there, leading soldiers in battle and training them in peacetime, leading by example and always, always – out front.

THE REVOLUTION TO THE CIVIL WAR

The history of the United States Army and of the noncommissioned officer began in 1775 with the birth of the Continental Army . The American noncommissioned officer did not copy the British. He, like the American Army itself, blended traditions of the French, British and Prussian armies into a uniquely American institution. As the years progressed, the American political system, with its disdain for the aristocracy, social attitudes and the vast westward expanses, further removed the US Army noncommissioned officer from his European counterparts and created a truly American noncommissioned officer.

The Revolution

In the early days of the American Revolution, little standardization of NCO duties or responsibilities existed. In 1778, during the long hard winter at Valley Forge, Inspector General Friedrich von Steuben standardized NCO duties and responsibilities in his Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States (printed in 1779). His work, commonly called the Blue Book, set down the duties and responsibilities for corporals, sergeants, first sergeants, quartermaster sergeants and sergeants major, which were the NCO ranks of the period. The Blue Book also emphasized the importance of selecting quality soldiers for NCO positions and served a whole generation of soldiers as the primary regulation for the Army for 30 years. In fact, part of Von Steuben’s Blue Book is still with us in FM 22-5, Drill and Ceremonies and other publications.

Von Steuben specified duties of the noncommissioned officer. The Sergeant Major served as the assistant to the regimental adjutant, keeping rosters, forming details and handling matters concerning the “interior management and discipline of the regiment.” The Sergeant Major also served “at the head of the noncommissioned officers.” The Quartermaster Sergeant assisted the regimental quartermaster, assuming his duties in the quartermaster’s absence and supervising the proper loading and transport of the regiment’s baggage when on march. The First Sergeant enforced discipline and encouraged duty among troops, maintaining the duty roster, making morning report to the company commander and keeping the company descriptive book. This document listed the name, age, height, place of birth and prior occupation of every enlisted man in the unit.

The day-to-day business of sergeants and corporals included many roles. Sergeants and Corporals instructed recruits in all matters of military training, including the order of their behavior in regard to neatness and sanitation. They quelled disturbances and punished perpetrators. They forwarded sick lists to the First Sergeant. In battle, NCOs closed the gaps occasioned by casualties, encouraged men to stand their ground and to fire rapidly and accurately. The development of a strong NCO Corps helped sustain the Continental Army through severe hardships to final victory. Von Steuben’s regulations established the foundation for NCO duties and responsibilities from 1778 to the present.

During the early stages of the American Revolution the typical Continental Army NCO wore an epaulet to signify his rank. Corporals wore green and sergeants wore red epaulets. After 1779, sergeants wore two epaulets, while corporals retained a single epaulet. From the American Revolution to World War II the noncommissioned officer received his promotion from the regimental commander. Entire careers were often spent within one regiment. If a man transferred from one regiment to the next, he did not take his rank with him. No noncommissioned officer could transfer in grade from one regiment to another without the permission of the General in Chief of the Army; this was rarely done. Without permanent promotions of individuals, stripes stayed with the regiment.

The Purple Heart

Three NCOs received special recognition for acts of heroism during the American Revolution. These men, Sergeant Elijah Churchill, Sergeant William Brown and Sergeant Daniel Bissell, received the Badge of Military Merit, a purple heart with a floral border and the word “merit” inscribed across the center. In practice this award was the precursor to the Medal of Honor introduced during the Civil War. After a long period of disuse, Badge of Military Merit was reinstituted in 1932 as the Purple Heart and is a decoration for members of the armed forces wounded or killed in action or as a result of a terrorist attack.

Rank Insignia

In 1821 the War Department made the first reference to noncommissioned officer chevrons. A General Order directed that sergeants major and quartermaster sergeants wear a worsted chevron on each arm above the elbow; sergeants and senior musicians, one on each arm below the elbow; and corporals, one on the right arm above the elbow. This practice ended in 1829 but returned periodically and became a permanent part of the NCO’s uniform before the Civil War.

In 1825 the Army established a systematic method for selecting noncommissioned officers. The appointment of regimental and company noncommissioned officers remained the prerogative of the regimental commander. Usually regimental commanders would accept the company commander’s recommendations for company NCOs unless there were overriding considerations. The Abstract of Infantry Tactics, published in 1829, provided instructions for training noncommissioned officers. The purpose of this instruction was to ensure that all NCOs possessed “an accurate knowledge of the exercise and use of their firelocks, of the manual exercise of the soldier and of the firings and marchings.”

Field officers and the adjutant frequently assembled noncommissioned officers for both practical and theoretical instruction. Furthermore, field officers ensured that company officers provided proper instruction to their noncommissioned officers. The sergeant major assisted in instructing sergeants and corporals of the regiment. Newly promoted corporals and sergeants of the company received instruction from the First Sergeant. The first sergeant of that time, like today, was a key person in the maintenance of military discipline.

THE CIVIL WAR TO WORLD WAR 1

The Civil War

During the 1850’s major changes occurred in US Army weaponry. Inventors developed and refined the percussion cap and rifled weapons. Weapons like the Sharps carbine added greatly to fire power and accuracy. The increased lethality of weapons did not immediately result in different tactics. The huge numbers of casualties in the American Civil War proved that technological advances must result in changes to battlefield tactics. Operationally, the Civil War marked a distinct change in warfare. No longer was it sufficient to defeat an enemy’s army in the field. It was necessary to destroy the enemy’s will and capacity to resist through military, economic and political means. This became the concept of total war. The war required a large number of draftees and unprecedented quantities of supplies.

During the Civil War, noncommissioned officers led the lines of skirmishers that preceded and followed each major unit. NCOs also carried the flags and regimental colors of their units. This deadly task was crucial to maintain regimental alignment and for commanders to observe their units on the field. As the war progressed, organizational and tactical changes led the Army to employ more open battle formations. These changes further enhanced the combat leadership role of the noncommissioned officer. New technology shaped the Army during the Civil War: railroads, telegraph communications, steamships, balloons and other innovations. These innovations would later impact the noncommissioned officer rank structure and pay.

Since its founding on 14 June 1775, the Army normally expanded in wartime with volunteers, with the professional soldiers forming the basis for expansion. The Civil War in particular brought a huge increase in the number of volunteer soldiers. This policy endured to some extent until world commitments and the stationing of troops overseas in the 20th century required the Nation to maintain a strong professional force.

In the post-Civil War era the Artillery School at Fort Monroe reopened to train both officers and noncommissioned officers. In 1870 the Signal Corps established a school for training officers and noncommissioned officers. Because both the Artillery and the Signal Corps required soldiers to have advanced technical knowledge to operate complex equipment and instruments, these were the first schools established. Efforts to provide advanced education for noncommissioned officers in other less technical fields, however, failed to attract supporters. Army leaders thought experience and not the classroom made a good NCO.

Military Life on the Frontier

During the Indian Wars period, enlisted men lived in spartan barracks with corporals and privates in one large room. Sergeants lived separately from their men in small cubicles of their own adjacent to the men’s sleeping quarters. This gave enlisted men a sense of comradeship, but allowed little privacy.

During the 1870s the Army discouraged enlisted men from marrying. Regulations limited the number of married enlisted men in the Army and required special permission to marry. Those men who did marry without permission could be charged with insubordination. They could not live in post housing or receive other entitlements. Still, nature proved stronger than Army desires or regulations. Marriages occurred and posts became communities.

Barracks life in the 1890s was simple, with card games, dime novels and other amusements filling idle time. Footlockers contained personal possessions, along with military clothing and equipment. Soldiers during this period maintained handbooks that contained a variety of information, including sections entitled, “Extracts from Army Regulations of 1895,” “Examination of Enlisted Men for Promotion,” “Take Care of Your Health,” “Extracts from Articles of War,” and others. In the back there were three sections for the soldier to fill in: “Clothing Account,” “Military Service,” and “Last Will and Testament.” Soldiers carried these handbooks for a number of years and provided an accurate record of the important events in his Army life.

The increase of technology which accompanied modernization greatly affected the NCO Corps during the last half of the 19th Century. The number of NCO ranks grew rapidly; each new advent of technology created another pay grade. The Army was forced to compete with industry for technical workers. In 1908 Congress approved a pay bill which rewarded those in technical fields in order to retain their services. Combat soldiers were not so fortunate. A Master Electrician in the Coast Artillery made $75-84 per month, while an Infantry Battalion Sergeant Major lived on $25-34 per month. Compare that with a Sergeant of the Signal Corps ($34 – $43 per month).

Enlisted Retirement

In 1885 Congress authorized voluntary retirement for enlisted soldiers. The system allowed a soldier to retire after 30 years of service with threequarters of his active duty pay and allowances. This remained relatively unchanged until 1945 when enlisted personnel could retire after 20 years of service with half pay. In 1948 Congress authorized retirement for career members of the Reserve and National Guard. Military retirement pay is not a pension, but rather is delayed compensation for completing 20 or more years of active military service. It not only provides an incentive for soldiers to complete 20 years of service, but also creates a backup pool of experienced personnel in the event of a national emergency.

NCO Guide

The Army began to explicitly define NCO duties during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The five or six pages of instructions provided by von Steuben’s Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States in 1778 grew to 417 pages in the 1909 Noncommissioned Officers Manual. While an unofficial publication, it was widely used and the chapters describing the duties of the First Sergeant and Sergeant Major included common forms, a description of duties, what should and should not be done and customs of the service. The Noncommissioned Officers Manual included a chapter on discipline that stressed the role of punishment in achieving discipline. The manual stated that the purpose of punishment was to prevent the commission of offenses and to reform the offender. However, this section repeatedly stressed that treatment of subordinates should be uniform, just and in no way humiliating.

The Modern Rank Insignia

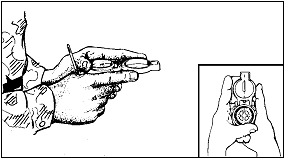

In 1902 the NCO symbol of rank, the chevron, rotated to what we would today call point up and became smaller in size. Though many stories exist as to why the chevron’s direction changed, the most probable reason was simply that it looked better. Clothing had become more form fitting, creating narrower sleeves; in fact, the 10-inch chevron of the 1880s would have wrapped completely around the sleeve of a 1902 uniform.

THE WORLD WARS AND CONTAINMENT

World War 1

World War I required the training of four million men, one million of which would go overseas. Corporals were the primary trainers during this period, teaching lessons that emphasized weapons and daytime maneuvers. Training included twelve hours devoted to the proper use of the gas mask and a trip to the gas chamber. After viewing the differences in American and foreign NCO prestige, American Commanding General John J. Pershing suggested the establishment of special schools for sergeants and separate NCO messes. The performance of noncommissioned officers in the American Expeditionary Force seemed to validate these changes.

In 1922 the Army scheduled 1,600 noncommissioned officers for grade reductions. Although this was necessary to reduce the total force and save money, it caused severe hardships for many noncommissioned officers, especially those with families. Also, post-World War I budget reductions and the Great Depression led to irregularities in pay: often the soldier received only half his pay, or half his pay in money and half in consumer goods or food.

The rapid pace and acceptance of technology during the late 1930s caused the Army to create special “technician” ranks in grades 3, 4, & 5 (CPL, SGT & SSG), with chevrons marked with a “T.” This led to an increase in promotions among technical personnel. The technician ranks ended in 1948, but they later reappeared as ‘specialists’ in 1955.

The typical First Sergeant of this period carried his administrative files in his pocket-a black book. The book contained the names of everyone in the company and their professional history (AWOLs, work habits, promotions, etc.). The book passed from first sergeant to first sergeant, staying within the company and providing the unit with a historical document. The first sergeant accompanied men on runs, the drill field, training, or the firing range. He was always at the forefront of everything the company did.

World War 2

With the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the United States found itself in another major war. Mobilization greatly increased the numbers of Army noncommissioned officers. Ironically, mobilization, combined with other factors, created a staggering growth in the percentage of noncommissioned officers to total forces. The proportion of noncommissioned officers in the Army increased from 20 percent of the enlisted ranks in 1941, to nearly 50 percent in 1945, resulting in reduced prestige for many noncommissioned officer ranks. Coupled with this growth in numbers the eight-man infantry squad increased to twelve, with the sergeant then staff sergeant, replacing the corporal as its leader. The rank of corporal came to mean very little, even though he was in theory and by tradition a combat leader.

Basic training in World War II focused on hands-on experience instead of the classroom. NCOs conducted all training for soldiers. After basic training, a soldier went to his unit where his individual training continued. The major problem was that the rapid expansion of the Army had led to a proportionate decrease in experienced men in the noncommissioned officer ranks. Making this condition worse was the practice of quickly advancing in rank soldiers who showed potential while combat losses reduced the number of experienced NCOs.

Fighting in the Pacific and Europe required large numbers of men. Millions of men enlisted and America drafted millions more. Still the Army suffered from manpower shortages. In 1942 the Army formally added women to its ranks. By 1945 over 90,000 women had enlisted in the Army. Women served in administrative, technical, motor vehicle, food, supply, communications, mechanical and electrical positions during the war. After the war women continued to serve in a variety of roles in the Army. As a result of the continued growth of technology, a new emphasis on education began in the post-World War II era. This emphasis encouraged the young soldier to become better educated in order to advance in rank.

NCO Education I

On 30 June 1947 the first class enrolled in the 2d Constabulary Brigade’s NCO school, located in Munich, Germany. Two years later, the US Seventh Army took over the 2d Constabulary functions and the school became the Seventh Army Noncommissioned Officers Academy. Eight years later AR 350-90 established Army-wide standards for NCO academies. Emphasis on NCO education increased to the point that by 1959 over 180,000 soldiers would attend NCO academies located in the continental United States. In addition to NCO academies, the Army encouraged enlisted men to advance their education by other means. By 1952 the Army had developed the Army Education Program to allow soldiers to attain credits for academic education. This program provided a number of ways for the enlisted man to attain a high school or college diploma.

Korea

In 1950 an unprepared United States again had to commit large numbers of troops in a war a half a world away. The North Korean attack on South Korea stressed American responsibilities overseas. Containment of communist aggression was the official policy of the United States. This meant that American commitments in Asia, Europe and the Pacific would require a strong and combat-ready professional Army. During the Korean War the NCO emerged more prominently as a battle leader than he had in World War II. The steep hills, ridges, narrow valleys and deep gorges forced many units to advance as squads. Korea was the first war America fought with an integrated Army. Black and white soldiers together fought a common foe.

In 1958 the Army added two grades to the NCO ranks. These pay grades, E-8 and E-9, would “provide for a better delineation of responsibilities in the enlisted structure.” With the addition of these grades, the ranks of the NCO were corporal, sergeant, staff sergeant, sergeant first class, master sergeant and sergeant major.

Vietnam

America’s strategy of containment continued after the Korean War and the Nation set a course to help its ally South Vietnam defeat communist aggression. In 1965 America made a major commitment in ground troops to Vietnam. The Vietnamese Communists fought a long drawn-out war, meant to wear down American forces. Because no clear battle lines existed it was often hard to tell foe from friend. In 1973 a formal cease-fire signed by American and North Vietnamese delegations ended American troop commitments to the area.

Vietnam proved to be a junior leader’s war with decentralized control. Much of the burden of combat leadership fell on the NCO. With a need for large numbers of NCOs for combat duty, the Army began the Noncommissioned Officer Candidate Course, with three sites at Fort Benning, Fort Knox and Fort Sill. After a 12-week course, the graduate became an E-5; those in the top five percent became E-6s. An additional 10 weeks of hands-on training followed and then the NCO went to Vietnam. However, senior NCOs had mixed feelings about the program (sometimes called the “shake-and-bake” program). Many of these senior NCOs thought it undermined the prestige of the NCO Corps though few could say they actually knew an unqualified NCO from the course.

Sergeant Major of the Army

In 1966 Army Chief of Staff Harold K. Johnson chose Sergeant Major William O. Wooldridge as the first Sergeant Major of the Army . The SMA was to be the primary advisor and consultant to the Chief of Staff on enlisted matters. He would identify problems affecting enlisted personnel and recommend appropriate solutions.

POST-VIETNAM AND THE VOLUNTEER ARMY

NCO Education II

After the US ended conscription following the Vietnam War, it became increasingly clear NCOs needed more sustained training throughout their careers. NCO education expanded and became formalized in the 70s and 80s. Today’s NCO Education System includes the Primary Leadership Development Course (PLDC), Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course (BNCOC), the Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course (ANCOC), and the US Army Sergeants Major Course (USASMC). The Sergeants Major Course first began in January 1973 as the capstone training for the Army’s most senior NCOs. The Sergeants Major Academy also operates three senior NCO courses outside NCOES that are designed to train NCOs for particular positions. These are the First Sergeant Course (FSC), the Battle Staff Course (BSC) and the Command Sergeant Major Course (CSMC). In 1986 PLDC became a mandatory prerequisite for promotion to staff sergeant. This was the first time an NCOES course actually became mandatory for promotion.

In 1987 the Army completed work on a new state-of-the-art education facility at the Sergeants Major Academy at Fort Bliss, Texas, further emphasizing the importance of professional education for NCOs. This 17.5 million-dollar, 125,000 square foot structure allowed the academy to expand course loads and number of courses. As the Noncommissioned Officer Education System continues to grow, the NCO of today combines history and tradition with skill and ability to prepare for combat. He retains the duties and responsibilities given to him by von Steuben in 1778 and these have been built upon to produce the soldier of today.

Grenada and Panama

The murder of Grenada’s Prime Minister in October 1983 created a breakdown in civil order that threatened the lives of American medical students living on the island. At the request of allied Caribbean nations, the United States invaded the island to safeguard the Americans there. Operation Urgent Fury included Army Rangers and Paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division. This action succeeded in the eventual reestablishment of a representative form of government in Grenada. After Manuel Noriega seized control of his country in 1983, corruption in the Panamanian government became widespread and eventually Noriega threatened the security of the United States by cooperating with Colombian drug producers. Harassment of American personnel increased and after a US Marine was shot in December 1989, the US launched Operation Just Cause. This invasion, including over 25,000 soldiers, quickly secured its objectives. Noriega surrendered on 3 January 1990 and was later convicted on drug trafficking charges.

The Gulf War

In August 1990 Iraqi military forces invaded and occupied Kuwait. The US immediately condemned Iraq’s actions and began building support for a coalition to liberate Kuwait. Iraq’s dictator, Saddam Hussein, ignored the demands of over 36 nations to leave Kuwait. In response, coalition forces began deploying to Saudi Arabia. On 12 January 1991 Congress authorized the use of military force to liberate Kuwait. Operation Desert Storm commenced 17 January 1991 as the coalition initiated an air campaign to disable Iraq’s infrastructure. After five weeks of air and missile attacks, ground troops, including over 300,000 from the US Army, began their campaign to free Kuwait. On 27 February 1991, coalition forces entered Kuwait City forcing Iraq to concede a cease-fire after only 100 hours of ground combat.

Somalia and Rwanda

In the early 1990s Somalia was in the worst drought in over a century and its people were starving. The international community responded with humanitarian aid but clan violence threatened international relief efforts. The United Nations formed a US-led coalition to protect relief workers so aid could continue to flow into the country. Operation Restore Hope succeeded, ending the starvation of the Somali people. US soldiers also assisted in civic projects that built and repaired roads, schools, hospitals and orphanages. A history of ethnic hatred in Rwanda led to murder on a genocidal scale. Up to a million Rwandans were killed and two million Rwandans fled and settled in refugee camps in several central African locations. Conditions in the camps were appalling; starvation and disease took even more lives. The international community responded with one of the largest humanitarian relief efforts ever mounted. The US military quickly established an atmosphere of collaboration and coordination setting up the necessary infrastructure to complement and support the humanitarian response community. In Operation Support Hope, US Army soldiers provided clean water, assisted in burying the dead and integrated the transportation and distribution of relief supplies.

Haiti

In December 1990 Jean-Bertrand Aristide was elected President of Haiti, in an election that international observers deemed largely free and fair. Aristide took office in February 1991, but was overthrown by the Army and forced to leave the country. The human rights climate deteriorated as the military and the de facto government sanctioned atrocities in defiance of the international community’s condemnation. The United States led a Multinational Force to restore democracy by removing the military regime, return the previously elected Aristide regime to power, ensure security, assist with the rehabilitation of civil administration, train a police force, help prepare for elections and turn over responsibility to the UN. Operation Uphold Democracy succeeded both in restoring the democratically elected government of Haiti and in stemming emigration. In March 1995 the United States transferred the peacekeeping responsibilities to the United Nations.

The Balkans

During the mid-1990s, Yugoslavia was in a state of unrest because various ethnic groups wanted a separate state for themselves. Serbia attempted through military force to prevent any group from gaining autonomy from the central government. Serbian forces brutally suppressed the separatist movement of ethnic Albanians in the province of Kosovo, leaving hundreds dead and over 200,000 homeless. The refusal of Serbia to negotiate peace and strong evidence of mass murder by Serbian forces resulted in the commencement of Operation Allied Force. Air strikes against Serbian military targets continued for 78 days in an effort to bring an end to the atrocities that continued to be waged by the Serbs. Serbian forces withdrew and NATO deployed a peacekeeping force, including US Army soldiers, to restore stability to the region and assist in the repair of the civilian infrastructure.

The War on Terrorism

Terrorists of the al-Qaeda network attacked the United States on September 11, 2001, killing nearly 3000 people and destroying the World Trade Center in New York City. The United States, with enormous support from the global community, responded with attacks on the al-Qaeda network and the Taliban-controlled government of Afghanistan that was providing it support. Operation Enduring Freedom with US and allied forces quickly toppled the Taliban regime and severely damaged the al-Qaeda forces in Afghanistan. US Army NCOs and soldiers continue to play a leading role in the war on terrorism and provide security to the Nation.

CONTEMPORARY OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT

Full Spectrum Operations

Today the Army’s operational doctrine covers the full spectrum of operations. That means stability, support, offense and defense operations. What that means to you is to conduct good training and make sure your soldier meets the standards. Effective training is the cornerstone of operational success. Training to high standards is essential for a full spectrum force; the Army cannot predict every operation it deploys to. Battle-focused training on combat tasks prepares soldiers, units and leaders to deploy, fight and win. Upon alert, initial-entry Army forces deploy immediately, conduct operations and complete any needed mission-specific training in country. Follow-on forces conduct pre- or post-deployment mission rehearsal exercises, abbreviated if necessary, based on available time and resources.

The Operational Environment

America’s potential adversaries learned from the Gulf War that to oppose US forces on our terms is foolhardy at best and may even be suicidal. As demonstrated by terrorist adversaries, we can expect that our enemies in the future will attempt to avoid decisive battle; prolong the conflict; conduct sophisticated ambushes; disperse combat forces and attempt to use information services to its advantage – all while inflicting unacceptable casualties on US forces.

The operational environment and the wide array of threats present significant challenges. Army forces must simultaneously defeat an adversary while protecting noncombatants and the infrastructure on which they depend. This requires Army leaders to be adaptive and aware of their environment.

Depending on your mission and location, you and your soldiers, or perhaps the local population may be the targets of a terrorist attack. An adversary may try to use you in an information campaign to destroy US resolve. The more vital your units’ mission is to the overall operation the more likely it is that an adversary will attempt to target you in some way.

The Information Environment

All military operations take place within an information environment that is not within the control of military forces. The information environment is the combination of individuals, organizations and systems that collect, process, store, display and disseminate information. It also includes the information itself. The media’s use of real-time technology affects public opinion and may alter the conduct of military operations. Now, more than ever, every soldier represents America – potentially to a global audience.

Technology enhances leader, unit and soldier performance and affects how Army forces conduct full spectrum operations in peace, conflict and war. Even with its advantages, the side with superior technology does not always win in land operations; rather, the side that applies combat power more skillfully usually prevails. The skill of soldiers coupled with the effectiveness of leaders decides the outcomes of engagements, battles and campaigns.

ARMY TRANSFORMATION

The NCO has a key role in Army Transformation, perhaps the premier role. As the Army becomes a more deployable, agile and responsive force, some units will reorganize, receive new equipment and learn new tactics. The NCO, as the leader most responsible for individual and small unit training, will build the foundation for the Army’s objective force. New technology enables you to cover more ground and maintain better situational awareness. But individual and collective tasks are more complex, requiring small unit leaders to coordinate and synchronize soldiers’ efforts and the systems they employ to a degree never before seen.

Our Army has always benefited from NCOs who could and did display initiative, make decisions and seize opportunities that corresponded with the commander’s intent. These qualities are more important than ever in Army Transformation. Despite technological improvement and increased situational awareness at every level – the small unit leader must still make decisions that take advantage of fleeting opportunities on the battlefield.