Table of Contents

Are you curious about the facts about recycled money?

Ever wondered about the whereabouts of old money? Have you ever observed how a bank typically issues pristine and neat banknotes, while the change you receive at a restaurant often comes in the form of crumpled bills?

Many individuals are unaware that the nation undergoes a daily process of refreshing its currency supply. This routine is necessitated by the wear and tear that paper money experiences—ripping, crinkling, disintegration, soiling, and mangling are all common occurrences. Mutilated money can result from various causes, such as fire, water, exposure to chemicals like explosives, damage from animals, insects, or rodents, and deterioration through burial.

Mutilated money is often the result of any of these common causes:

- Fire

- Water

- Chemicals like explosives

- Animal/insect/rodent damage

- Deterioration by burying

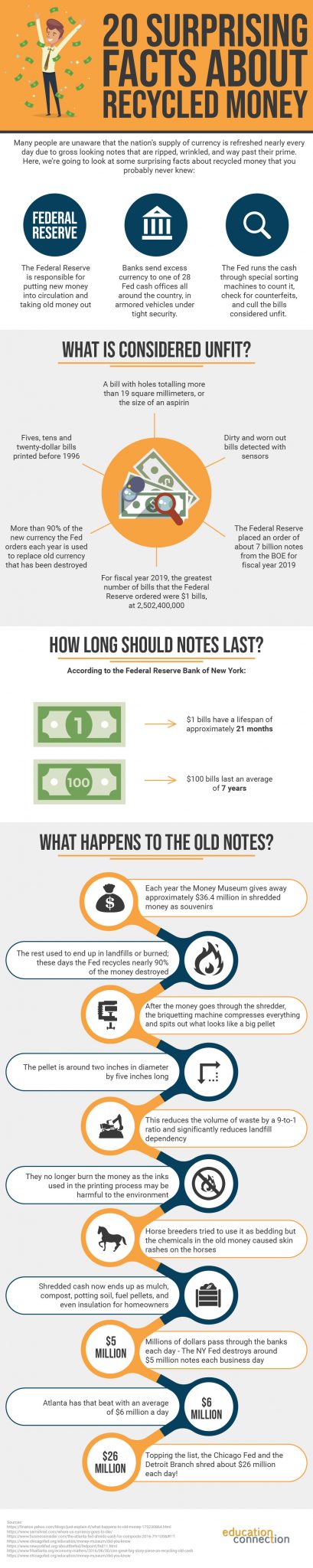

The responsibility of injecting new money into circulation and retiring old, damaged currency falls upon the Federal Reserve. However, it’s important to note that the Federal Reserve doesn’t physically produce new money. Instead, the two key agencies responsible for creating new currency in the U.S. are the Bureau of Engraving (BEP) and the United States Mint.

These agencies adhere to stringent rules governing the production of new coins and currency. Simultaneously, there are regulations specifying the criteria that render money unfit for use, preventing its acceptance by ATMs or other electronic readers.

As a result, the Federal Reserve engages in the daily process of introducing fresh currency into circulation and withdrawing damaged money. According to some reports, the print order for CY 2024 ranges from 5.3 billion to 6.9 billion notes.

Does the Fed Recycle Money?

When a note is authentic but too worn for recirculation, the Fed destroys it. In the past, it would burn or shred old bills, dumping them in landfills. In fact, The Federal Reserve used to send the shredded cash to landfills, but now 90% of the money is recycled.

But this process is changing. Going green, you could say. Take San Francisco, for instance. There, the Federal Reserve Bank partners with a green facility. They burn shredded currency in an eco-friendly power generation plant. The plant then provides electricity for local businesses and homes.

Can You Take ripped Money to the Bank?

Some banks accept and exchange soiled, dirty, worn and torn bills. But they set rules about what they take and what they don’t. These rules may follow BEP guidelines for mutilated currency:

- The note is more than 50 % identifiable as United States currency

- Has enough remnants of security features (like serial numbers)

- More than half the original note remains

The Treasury also has a method in place to review claims made where you can’t check the above off your list. To file a claim, you need to submit the currency and details of how it became mutilated.

Here’s What Happens to Old Currency

Here are some other some surprising facts about recycled money that you may not know:

- Banks send excess currency to one of 28 Fed cash offices all around the country, in armored vehicles under tight security.

- The Fed runs the cash through special sorting machines to count it, check for counterfeits, and cull the bills considered unfit.

- The Federal Reserve rejects incorrect denominations, suspected counterfeits, and non-machine-readable notes.

- Every year the Treasury Department handles about 30,000 claims for mutilated money. It redeems mutilated currency valued at over $30 million.

- In one year alone, the Federal Reserve shredded 7,000 tons of retired money.

What is Considered Unfit?

- A bill with holes totaling more than 19 square millimeters, or the size of an aspirin

- Dirty and worn out bills detected with sensors

- Fives, tens and twenty-dollar bills printed before 1996

- More than 90% of the new currency the Fed orders each year is used to replace old currency that has been destroyed

- For fiscal year 2019, the greatest number of bills that the Federal Reserve ordered were $1 bills, at 2,502,400,000

- The Federal Reserve placed an order of about 7 billion notes from the BOE for fiscal year 2019

How Long Should Notes Last?

According to the Federal Reserve the lifespan of notes varies by denomination. It will also depend on how many times each one passes between users. Smaller bills tend to change hands more often, so it doesn’t endure as long as the larger bills (like the $100).

| Denomination | Estimated Lifespan* |

| $1.00 | 6.6 years |

| $5.00 | 4.7 years |

| $10.00 | 5.3 years |

| $20.00 | 7.8 years |

| $50.00 | 12.2 years |

| $100.00 | 22.9 years |

What Happens to The Old Notes?

- Annually, the Money Museum distributes approximately $36.4 million in shredded currency as keepsakes.

- In the past, the remaining shredded money was either sent to landfills or incinerated. However, the Federal Reserve now recycles nearly 90% of the decommissioned currency.

- Following the shredding process, a briquetting machine compresses the remnants into a sizable pellet, measuring approximately two inches in diameter by five inches in length.

- This compression results in a 9-to-1 reduction in waste volume, significantly diminishing reliance on landfills.

- Abandoning the practice of burning money is due to environmental concerns regarding potentially harmful inks used in the printing process.

- Attempts by horse breeders to use shredded currency as bedding proved unsuccessful due to the chemicals causing skin rashes in horses.

- Presently, shredded cash finds new life as mulch, compost, potting soil, fuel pellets, and even home insulation.

- Each business day, the NY Fed obliterates around $5 million in notes, while Atlanta surpasses this with an average of $6 million daily.

- At the forefront, the Chicago Fed and the Detroit Branch collectively shred approximately $26 million every day!